Mabini Projects

Cumulus Blimp:

A Transnational Platform of Discourse

OPENING:

Friday, November 24, 2017, 6 pm

EXHIBITION DATA:

November 24 to December 22, 2017

The discussion of gender and gender politics constitutes a significant trend in contemporary thought. Filipina Bree Jonson and Israeli Michal Baratz Koren’s works invigorate an exploration of this theme via their points of departure and arrival, comparison and contrast. Both Baratz Koren’s cinematically-staged photographs and Jonson’s collections of flora and fauna, sculpted or painted in oils, are posed for an encounter with the viewer. Telling epic stories of females under the pressure of patriarchy, with men as fathers, husbands, lovers, and kings, it seems that the moments captured in Baratz Koren’s works are critical for their characters. Are Jonson’s subjects also experiencing pivotal moments of transition or strain? It is likely that for her assorted plants and sea-life, the everyday business of being is itself a struggle. This nonhuman point of reference then calls our assumptions about Baratz Koren’s women into question again. As each informs the other, both artists invite the viewer to question the significance of the framing of their pieces: what it illuminates and what it obscures. Baratz Koren and Jonson certainly crate with an eye to similar focal points: how metaphor operates as animals and humans stand in for something else; the use of naturalism; the corporeal body and its beauty or grotesqueness. Through these frames, further correspondences can be investigated.

Jonson’s previous works feature creatures hunting and eating each other; her sea creatures have been understood as stand-ins for femininity, representing both the binaries of predator/prey and endangered/dangerous. Amidst these tropes of the hunt, it would be easy to interpret the collection of pieces presented here as simply representative of the female form: wild, seductive and savage, in need of taming. But how overworked this old trope is. Like a beast of burden, it has carried the feminine mystique from the first revolutionary 1700s assertion of women’s equality (against Enlightenment thinking that located women/beasts on the same irrational plane) to 1980s evocations of Mother Earth drowning in chemicals and war. Yet femininity must be allowed to be something more, something less. For this reason, Johnson’s oeuvre asks viewers to question why we are so eager to read the yawning opening of a Rafflesia flower or a sea anemone as vaginal, ready to suck the unsuspecting up into its unknown depths – why we unhesitatingly attribute such meanings to her works.

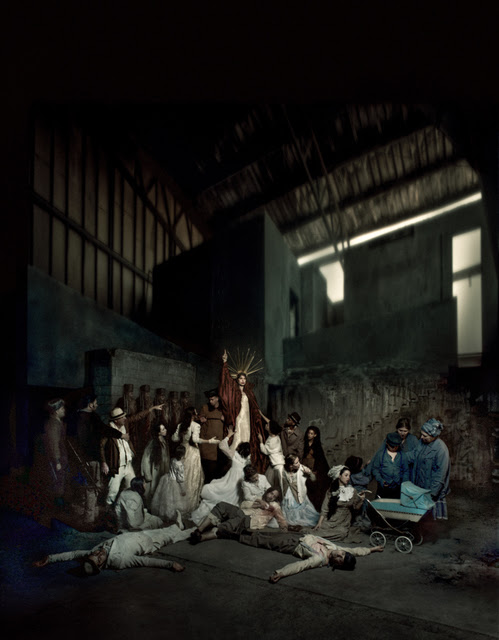

Perhaps answers to these questions reside within Baratz Koren’s photographs. This collection surveys scenes of darkness and chiaroscuro, betrayal, hiding, and salvation. Here are five females: Eve, Rachab, Bathsheba, Delilah, Hagar, and Jezebel. Must the women’s bodies, which constitute the focus of these staged photographs, be read as sensual and sinister? Emphasizing myths of women in a patriarchal world, the works inspire viewers to ask if these women are framed and silenced, or given voices. In the poetry of Carol Ann Duffy, whose The World’s Wife presents legends and fables from the point of view of the women contained therein, Delilah cuts Samson’s hair because he asks her to teach him to be tender, lamenting that all he can do is “be strong.” It might be easy to say this is just another retelling of a story in which a woman does something because of a man. But Delilah is the one telling the tale, (or at least, a poet speaking with her voice), not the seventh book of the Christian and Hebrew bibles condemning her as the dangerous seductress who causes Samson’s downfall. In this light, it may be that Barazt Koren’s works invite the viewer to see their subjects like the subjects of Duffy’s poems – telling their own stories. It may be that Jonson’s sea creatures too tell their own stories.

We constantly anthropomorphize nature. Yet Jonson’s careful portrayals are not simply attempts to attribute human features to her subject matter. Thus in reading her works as representations of seductive females, we are projecting our own anxieties onto her references to female anatomy. Yet avoiding animals’ human associations is an impossible task. The seeing “I” – whether that “I” be the artist or viewer – will read onto its object whatever forces animate its own subjecthood. In other words, we will read and interpret what we see in the particular ways we have learned to read and interpret all things according to our own sociocultural contexts, in particular historical moments. This means that as viewers living in a time of intensifying gender awareness, we will continue to gender Jonson’s sea creatures with our gaze.

Our gaze alike rests on Baratz Koren’s women. Her photography inverts photorealism, and instead of camera-ing with paint, she paints with her camera. Staging and lighting create a sort of soft, Pre-Raphaelite quality of luminosity, while the artist’s focus on women in this selection of images furthers the association – with long hair flowing and breasts apparent in a manner which certainly doesn't invoke a call to #freethenipple. But if one knows about the Victorian era’s treatment of women, one knows of the virgin whore dichotomy, the ideal of the “domestic angel,” and women’s constrained social position within the home, held up as the ideal even while thousands of working-class women were entering the work force, made invisible. How then should the viewer take the scene before them? Were the subjects waiting there to be found and photographed, or did the photographer happen to come along at the perfect moment?

Wildlife photography strives to make the viewer imagine the second scenario. Do Jonson’s paintings do the same? An uneasy peace hangs in the balance as what is captured within the frame mirrors the artist, whose intimate creations are captured within the gallery. Each wants to be seen, but they do not want to be misunderstood as women have been throughout history.

All that is clear from the works of these two artists is that their themes are not the struggles of humankind. In eliding and minimizing the male, in representing the writhing of the sea, the struggles of women, these creators frame the I and the Other. Both are creating works as women and as artists. But we must be careful not to universalize this into some uniform conception of the project of art and womanhood. After all, there is no “woman” – no biological truth, no homogenous gender presentation, no ubiquitous value system. Though we might not see it, each female-identifying person is different. Each anemone is different. Each life is its own.

Text by Heather Pennington